The theme of my exhibit is sculpture

across cultures. Humans create sculptures for many reasons, one being to

immortalize an important figure. This is shown through many Ancient Greek and Ancient

Roman sculptures. Not all Greek sculptures have survived, and many seen at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art are Roman reproductions. These sculptures were

crafted from marble with the finest attention to detail. Sculptures of gods

display perfect human form. African sculpture often depicts the opposite. Faces

with exaggerated facial features dominate this genre. The materials used in the

creation of these sculptures are more basic. For example, many African

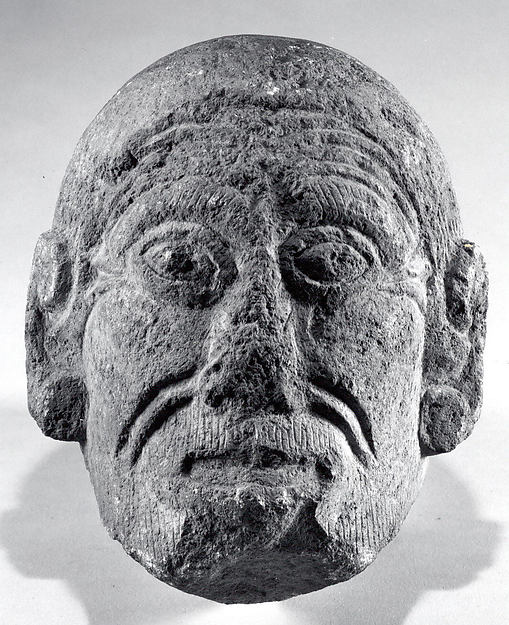

sculptures are made of wood. Mexican sculptures possess the quality of intricate

carvings on the facial regions. The detail of these carvings make it seem as if

the sculpture was not of a human face, but that of a mask. The medium used with

many Mexican sculptures is limestone. Different regions produce different types

of sculptures. Cultural ideas and beliefs are embedded within these sculptures.

Many sculptures seen from Ancient Greek, Mexican, and African cultures depict

deities. This leads us to conclude that these deities must have had an

important part in everyday life, otherwise the sculptures would not have been

created in the first place. Different regions also produce different materials

for creating work. Greek and Roman sculptures are dominated by the materials of

bronze and marble. African sculptures, on the other hand, make use of wood and

ceramics. The difference between the sculptures does not relate to the

advancement of each culture. Rather, these materials represent what was

presently available at the time of creation. This exhibit takes you through

three different cultures. Each culture has a different take when it comes to

creating a sculpture. Look at these sculptures as a window into the past, and

see how different times were back then in relation to today.

Polykleitos, "Marble statue of Hermes," 1st or 2nd Century, Greek/Roman

Restoration: Vincenzo Pacetti, "Hope Dinoysos," 27 BC - 68 AD, Greek/Roman

Artist Unknown, "Marble statue of Aphrodite," 1st or 2nd Century AD, Greek/Roman

Artist Unknown, "Female Figure," 19th-20th Century, African

Artist Unknown, "Monumental Figure," 9th Century, Mexican